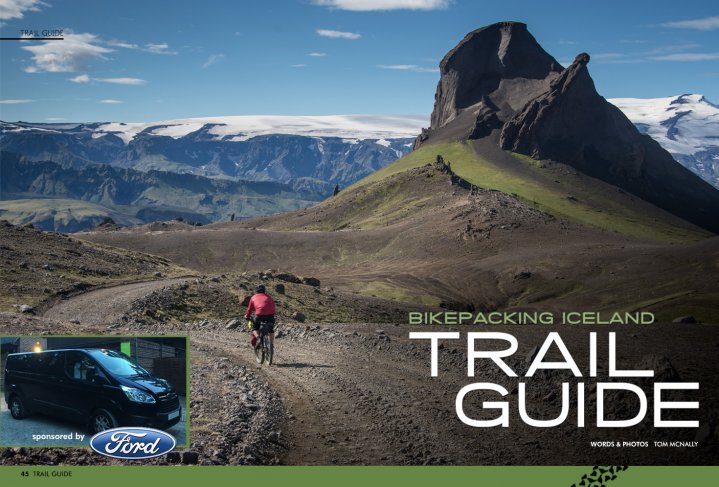

Trail Guide - Iceland Bike-Packing

Issue 45 / Fri 16th Dec, 2016

We get well and truly off the beaten track as we head far north to the land of fire and ice. Tom McNally straps everything he needs to his bike and sets off for an adventure of a lifetime into the interior and lives to tell the tale.

The view was a panorama like nothing else I had ever seen. All along the horizon distant ice caps glinted in the sun underneath bluebird skies. Vivid green slopes draped in ribbons of snow soared upward to rocky summits, the only sound the hiss of a gentle breeze. My eye traced the line of the trail from beneath our feet, swooping down the broad ridge in front of us, descending steeply all the way to the plateau and into the distance. This was going to be special.

After the first few days riding, Simon and I had become familiar with how the loose volcanic terrain behaved under our wide tyres and we began descending like we meant it. As we tore down toward the plateau, I stole a quick look at the view. It felt like I should pinch myself, surely this was a dream. Despite the physical exertion of managing the bike at high speed, I could feel tingles running down my spine, and a sensation of absolute euphoria washed over me.

Everything had come together; we were riding awesome trails, in awesome weather, deep in the mountainous interior of Iceland. What’s more, we were travelling entirely self-sufficiently, the bikes carrying all the food, shelter and spares we needed. No shuttles, no support, just us, shredding through the most jaw-dropping landscape I had ever seen.

Many people mistakenly regard ‘bikepacking’ as a recent development within mountain biking. In reality, off-road cycle touring has been around for as long as bikes have. As early as 1886, the US military began experimenting with the use of bikes as transportation for lightly armed infantry across mixed terrain. It was found to be highly effective, even more so than horses until their attention was soon diverted, however, by the advent of the automobile.

In recent times, the wider availability of ultra lightweight camping equipment and specialised bike luggage has revolutionised off-road touring, and it has seen an explosion in popularity. With the right equipment and bike choice, it is now possible to carry everything needed to live pretty comfortably without need for a touring rack or weighty panniers. A lighter, better-balanced setup means riding loaded bikes on technical terrain is now fun, as opposed to bouncing down stuff barely in control wondering what is going to break first.

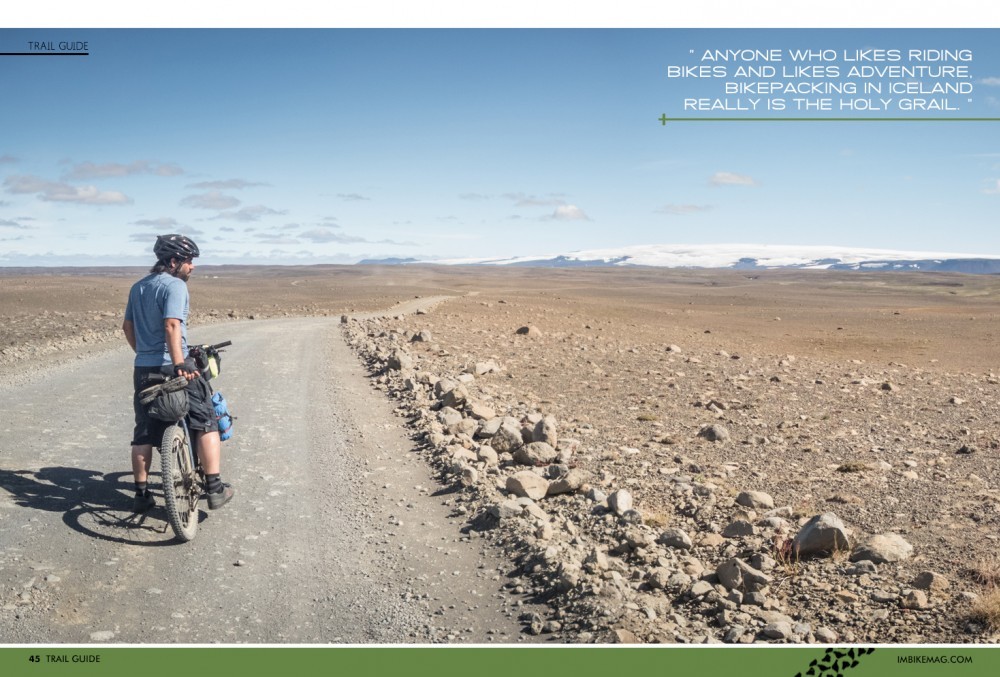

Occupying a weather-lashed and isolated position in the far North Atlantic, Iceland has become something of a holy grail for bikepackers. It is approximately the same size as Scotland, but its diminutive size is deceptive. The almost uninhabited interior of the island is a seemingly vast landscape of multi-coloured mountains, volcanic wastelands and ice caps. A network of dirt roads and trails makes this serious yet surreal environment accessible to those with the right transport and adequate supplies.

Much of this network is closed for most of the year and some roads can even be impassable due to snow until late June. And so, last July, prime time for travelling in the interior, my friend Simon and I found ourselves on a flight bound for Reykjavik. We were as excited as dogs on the way to the beach. Would it live up to the hype?

Our journey from Reykjavik began by bus and of the bus operators in Iceland, Straeto is the only one that will take bikes long distance for no extra charge. We quickly learned a valuable lesson: Get to the stop early, strip large luggage off the bikes and be super friendly to the driver. Each bus has a rack on the back just about big enough for three bikes but once it’s full, it’s full. Sometimes the drivers will let you squeeze bikes underneath, but not always.

Iceland has one big ring road, the N1, circumnavigating the whole island. From here the network of minor roads begins to encroach inland, but it is not far before the gravel starts. It was on the N1, at the junction with the F209 near Vik, that we disembarked the bus with a tangle of bikes and six days worth of food and fuel. It was nine o’clock at night but still very much light. Good job really, we had a fair bit of distance to cover before we found a spot to camp under a huge golden moon overlooking a vast beach of black sand.

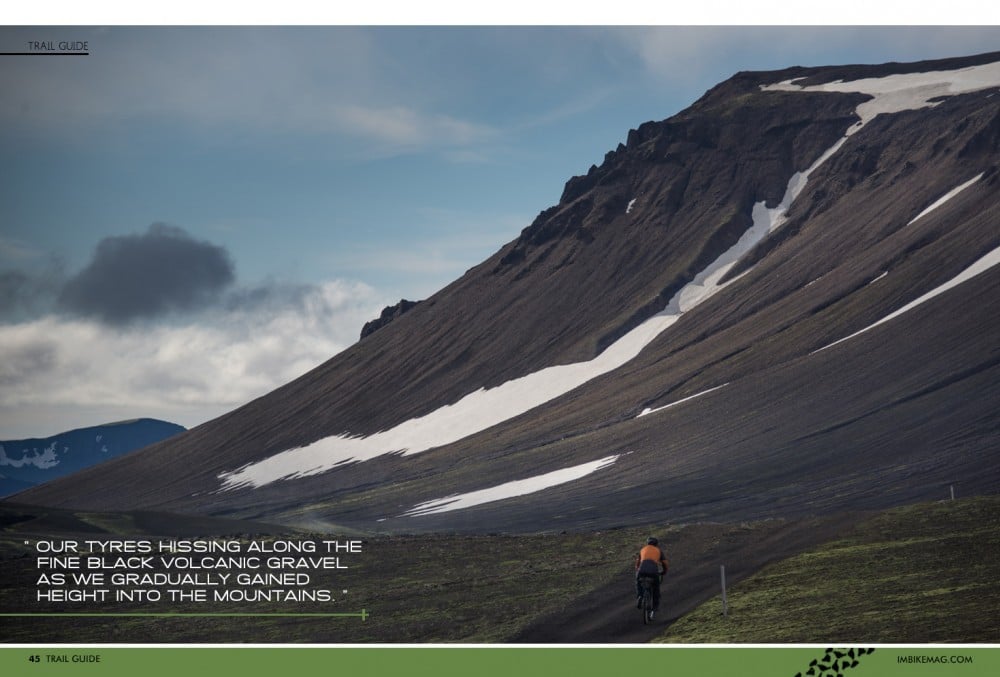

Over the next few days, we headed north, our tyres hissing along the fine black volcanic gravel as we gradually gained height into the mountains. Though it didn’t rain, water was everywhere. Huge torrents thundered down through a landscape of vivid green moss, reaching the valley bottoms in wide meandering channels through which we had to cross. We had brought sandals thinking we could swap footwear, but after the umpteenth crossing we simply couldn’t be bothered and gave up on dry feet until we made camp each night. A bit of talcum powder and insulated tent booties became worth their weight in gold.

We swung west along the F208 and F225 to reach the outpost of Laudmannalaugar, famed for its brightly coloured rhyolite mountains and geothermal activity. Trying to ignore the crowds, we pitched the tent before making a beeline for the hot springs and set about easing tired muscles with the aid of some cold beers.

Initially, we had planned to ride the legendary Laugavegur trail heading from here all the way south to the coast. It had been ridden before, and we had found a handful of trip reports online. Not one for the faint-hearted it includes lots of bike carrying, both up, and down (depending on bravery levels!) the steep volcanic terrain. As it is a highly popular hiking route, deservedly so, it can be very busy. The crowds forced our hand, and it was an easy decision to continue west the next day, before turning south onto a network of more remote tracks and bridleways. We gained yet more height, feeling a bit more committed our situation had all the ingredients of a proper adventure. The wind increased, and the temperature and visibility dropped and all of a sudden we felt very alone, on intermittent trails, high up in an intimidating volcanic landscape. The right equipment, sound decision making and accurate navigation took on ever-greater significance.

After a night camped outside a mountain hut filled with hikers, we awoke to find the wind had swung from the north bringing cold temperatures but bright sunshine and bluebird skies. Waking up, seeing the sun on the tent, looking at the map and knowing we were about to experience some of the best riding ever was a feeling I will never forget. Looking back, those two days are still a blur of huge volcanic vistas, forearm burning descents, sunburn, sketchy river crossings and face ache from smiling so much.

We emerged along the rock-strewn glacial valley of Porsmork and headed round to Skogar, immensely tired and extremely satisfied. The next day after a ride on black sand and gravel to the much-photographed crashed DC3 aircraft; we caught the bus to collect our cache of food and begin the next loop.

This time we were dropped at Reykholt, aiming to complete a circuit of the Langjokull ice cap. A soul-sapping slog on tarmac into a strong headwind saw us dodging hordes of tourists around Geysir and Gulfoss. As soon as we turned right out of the car park at Gulfoss the traffic stopped, the gravel started, and we breathed a sigh of relief. We had joined the Kjalvegur route.

Many people travelling by bike choose to undertake a complete crossing of the island. The most popular route takes the infamous Kjalvegur. This ancient route has been used as a Summer crossing from as early the 9th century when Iceland was first settled.

Our relief was short-lived, and over the next few days, the routes reputation was realised with mile after mile of washboard gravel roads, fierce winds, dust and a surprising amount of traffic. One morning we bumped into a group of friendly fat-bikers from Canada, who highly recommended the area of Kerlingarfjoll with quality hot springs and views rivalling Laudmannalaugar. Unfortunately, the burden of our return flights made a diversion unfeasible in the time remaining.

Continuing on the F35 held zero attraction for us, and as planned we turned west at the northern tip of the Langjokull ice cap onto a deserted bridleway. We made camp next to a small river and being the only people for miles around was a position we were becoming very happy with.

The riding from here began to get technical. In our planning, we had overlooked a traverse across an area known as the Storisandur. A full day of managing loaded bikes on a very rocky and undulating trail left us tired. We were nearing the end of the trip, and it was beginning to show. After a relatively deep and chilling river crossing, we were hit with our first taste of truly Icelandic weather as a big rain storm rolled in. The noise of rain on our hoods was deafening, and we were soaked to the skin within minutes. With eighteen kilometres remaining until an actual campsite we decided to push on. After just five minutes it became apparent we were going to get dangerously cold very quickly. We stopped, got the tent up with numb fingers and put a brew on. Grinning at each other through chattering teeth we were glad we made the right decision.

The next morning couldn’t have been more of a contrast and saw mile after mile of smooth downhill in bright sunshine. It was surreal to see the landscape zipping past so quickly after all the concerted effort to cover even relatively small distances in the previous few days. We were in Borganes early enough for some well-earned refreshments, before catching the bus back to Reykjavik. I’m sure we smelled pretty bad but past caring we fell into a deep, slightly drunk, probably slightly stinky sleep.

Back in Reykjavik, it was a relief to have finished and to eat decent food and sleep in a normal bed, but all too quickly came a real feeling of sadness that the trip was over so soon. We had been in Iceland for almost two weeks. Ten days were spent in the saddle riding hard, yet it felt like we had only just scratched the surface. There is so much potential; I can’t wait to get back.

Travelling through awesome places by leg power alone, carrying everything you need to live comfortably is tough to beat. To anyone who likes riding bikes and likes adventure, bikepacking in Iceland really is the holy grail. Book your flights; you won’t regret it.

Top Tips for biking in Iceland

Iceland is busy in the summer, and getting increasingly so. If you do want to visit touristy places near the ring road, consider going at unsociable times. It will still be light!

Take loads of money! As an example, gas was the equivalent of £11 for a 230gm cylinder. Don’t get me started on beer prices. Luckily camping isn’t too expensive.

Routes can often be closed due to landslides, flooding, snow or even geothermal activity. Local knowledge is invaluable and be flexible. It is always worthwhile having a Plan B.

Take a mask and earplugs. In July/Aug it doesn’t really get dark, and it can be hard to get to sleep. Youth hostels can be noisy places too.

Take a strong tent with a big porch. Iceland can be very wet and very windy. We valued having space to cook and store wet kit more than saving a few hundred grams. Thanks to Fjallraven for our Abisko Shape 3, which was perfect for the job, a portable bomb shelter.

Lube…regularly. It is also worth taking a small can of degreaser and a rag. Iceland is where drive chains go to die. Volcanic grit and endless river crossings will play havoc with moving parts.

Planning Resources

Icelandic Mountain Biking Club - http://www.fjallahjolaklubburinn.is/english

Bikepacking.com - http://www.bikepacking.com

By Tom McNally