Ten Things I Learned In B.C.

Issue 73 / Wed 14th Dec, 2022

Visiting British Columbia is an experience. From bears to river crossings, there's a manual for it all. Read Tim’s ten top tips here.

British Columbia a mecca for modern mountain bikers and on many peoples to do list. The riding is epic, the people are friendly and it’s one of the few places on earth where you can find true wilderness. I went riding in the Chilcotins and came back with ten life lessons learned.

Grizzly bears are a real thing

You’re not allowed to kill them. Which is fair enough. They, however, are allowed to kill you. In order to improve the chances of not getting your sternum opened with the swipe of a claw, all riders on our trip are required to carry bear spray. This comes in the form of a small fire extinguisher-type thing, slightly bigger than a can of deodorant, which is filled with concentrated pepper spray. Good news? Bears hate pepper spray. Bad news? You won’t know how much any actual bear hates it until it's less than ten feet from you, by which time you may well have soiled yourself, fallen to the ground blubbing, or foolishly tried to run. We also have to make noises all the time - shouting ‘hey bear’ and stuff - and I carry a small bell that rings all the time it’s unlocked, which drives everyone else crazy, so I mostly don’t use it.

We actually see two different grizzly bears on two different days, but both of them seem to consider a noisy bunch of people holding bikes to be too much trouble to bother with. Which is, you know, a massive relief.

Starting a ride by getting on a plane is cool

Our first trail starts at a place called Lorna Lake, at the Southern end of the South Chilcotin mountain range, but we can’t get there by car, or on foot, or even on bikes. We get there by packing all our bikes and kit into a small De Havilland float plane, which is 61 years old, and trusting our excellent pilot to take off from the surface of Tyaughton Lake, some 45 minutes south of our trailhead. She expertly flies us over mountains, creeks and forests before dropping us off at a tiny jetty on Lake Lorna and leaving us to our own devices.

It’s about the most adventurous beginning to a bike trip I’ve ever had. It feels like something out of an Indiana Jones movie, with the added jeopardy of trying to look excited for photos while doing your best not to throw up over four other people and the back of the pilot’s head.

When we’re all gathered there, the plane’s turned around and taken off for home, and we’re all looking at the steep mountain range, total lack of human activity and imposing skies, it’s a sobering moment - thankfully lightened when someone produces a small bottle of whisky to toast the start of the trip.

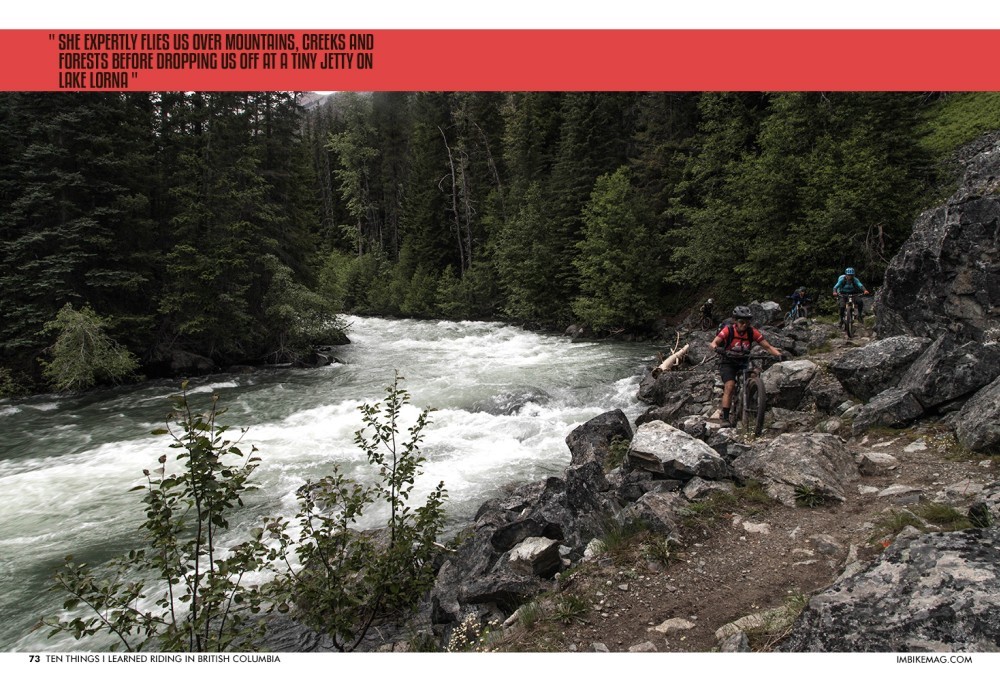

Dropping your bike in a fast-flowing river would suck

This trip is on some well-established trails, and takes us from camp to camp over three days, with a lot of climbing, some hike-a-bike, and - as it turns out - many river crossings. Due to the presence of late snow - the local peaks are mostly still capped in white - the meltwater has swollen these creeks and rivers more than usual and they’re raging. We can’t ride through them, or around them, or walk the bikes. We have to hoist the bikes over our heads, wade waist-deep into freezing rapids, and carry everything over one by one.

It’s unhelpful, but also unavoidable, to consider what might happen if this goes wrong, but it would likely include:

- Some form of bodily injury as you fell into sharp rocks

- Being totally soaked from head to foot, including all your dry clothes, food, tools communications equipment

- Watching in horror as your bike rushed away downstream, in a way that would make it impossible to retrieve without further injury to yourself or others, stranding you in the wilderness until you could limp into camp and be helicoptered out

- In my case, having to explain to the nice people at Rocky Mountain that the ten grand ultra-light Element C90 bike they kindly lent me is now part of some remote dam because I dropped it in the river

All of this adds considerable spice to the ride. I recommend it.

The downhills last for a really long time

No disrespect to UK riding - it’s 99% of the fun I get to have on a bike - but when it comes to sheer length of descent, actual mountains are hard to beat. The descent from the top of our first mammoth, 4000ft climb just seems to keep going, and going, and going. And it’s like a greatest hits of natural trail riding. Loose fields of scree one minute, slippery roots and creek-splash dips the next, before dropping us into tight corners and rock drops, then hurling us out into open fields of Alpine flowers.

As we make our way down towards the first camp of the trip, in Bear Paw, the scenery and riding just keep getting better and better - we’re whooping and hollering like little kids, all thoughts of bears and sore legs banished in a whirl of speed and adrenaline.

It’s almost disappointing when it’s over and we roll into camp. Almost.

A cheeseboard is always welcome

This particular backcountry adventure is with the fine folks at Tyax, who organise MTB trips like this one, and helidrop rides, and hiking, and a bunch of other stuff. Not to mention they pay people to stay in the camps we’re using all summer, as hosts, and these lovely people have prepared for our arrival. Tents are up, with the most comfortable sleeping bags I’ve ever slept in cleaned and ready, on solid beds. Our pre-ordered beer and wine is cooling in a crate in the nearby creek. Dinner is cooking. And, slightly ridiculously, there’s a table laid with a cheeseboard, a selection of cured meats, and some hummus as well.

You may be thinking that this is far from adventurous, and that if I were a real backcountry rider I’d have packed all my own gear on the bike, and spent the first night eating charred deer meat off a stick after hunting it myself. You might well be right, but after seven hours in the saddle, I guarantee you wouldn’t say no when someone offers you a slice of Brie with one hand and a creek-cooled IPA with the other.

You will not wish for a heavier bike

In normal life, I like as much travel as I can get. I don’t mind a slow climb on a bigger bike, and I’m not the world’s greatest jumper, so I want all the bounce that’s going. But despite the hosted camps, we’re all still carrying 3+ litres of water, an extra water bottle, tools, all our clothes, food for the day, etc, and pushing/carrying the bikes in stretches of over an hour at a time. So the Rocky Mountain Element C90 I’ve been lucky enough to procure for this adventure - weighing in at just over 24lbs - is a choice I don’t regret once for the entire trip. The 29” wheels make sense for long XC stretches, there’s just enough travel not to rattle me to death, and it climbs like a dream. Even when we hit some spicy trail features in North Vancouver before flying home, and I mangle them pretty badly, it doesn’t bottom out. Don’t go burly, people. Think of your spine.

Ninja-like packing skills are essential

There didn’t seem much point in checking luggage, as I had to carry everything I needed in a riding pack anyway, but it took some stuffing to get everything in there anyway. Even with resigning myself to wearing the same shorts, top, gloves, shoes and pads for the whole of the riding part, that still meant carrying a decent jacket (I had a lovely Berghaus Goretex number I bought especially, which l left on the train to Gatwick, so had to buy a new Troy Lee Designs waterproof at bike shop prices), another top for the evening, some trousers, a pair of trainers, tools, bear spray, phone, washbag, medicine and other bits and pieces. I used every inch of space and filled every pocket of an Evo Explorer Pro 26, and it was just about enough, but I still needed to buy a fresh t-shirt for the flight home or risk being ejected for reasons of six-day bike stink. Also - Merino wool is your friend. A Nukeproof baselayer lasted six days of riding, multiple river dousings, beer spillage and more and still basically smelled OK.

The more the merrier

We had a group of ten riders total. Initially, I thought that might be an issue, because the more people you have, the slower you go, and the greater your chances of being held up by mechanicals, tiredness, or being stuck with someone you can’t stand for days on end.

It turned out to be one of the best things about the whole trip. I knew some people, but we were all connected by someone, and the mixture of men and women, different abilities, esperice levels and ages made the whole thing feel like even more of an adventure. Spending three days having the time of your life with a bunch of other people all doing the same is a great way to bond. We also managed 18-20 hours of backcountry riding without a single puncture, serious mechanical or injurious fall, no-one ran out of energy and we all got on really well. So experience it with as many people as you can.

Prepare your hands

It’s always the hands that get me. I live in a part of the UK where the most elevation we can get locally is about 300ft. So my downhill runs are short. Every time I go riding somewhere with longer descents, my hands end up hurting more than any other part of my body, as I’m not used to gripping the bars and the brakes for so long. Never was this more evident than on the last day of the trip, where a 20K trail felt like one long speedy singletrack descent, straight enough in places to encourage the fastest possible lines. We actually climbed 2000ft that day, but all in the form of steep steps back up the trail so the descent could begin again, with the raging rapids of Gun Creek matching our pace to the right as we plunged in and out of forests, hopped off trail rocks, bounced over roots and sprayed off-camber scree down the riverbank.

Next time, I’ll spend the month beforehand squeezing a tennis ball or something.

British Columbia might just be MTB paradise

So as well as the three days backcountry riding in the Chilcotins, I also managed to pack in a full day’s warm up riding in Squamish, a half day of slabs and rock rolls in Pemberton and an amazing day on the crazy woodwork of Mt. Fromme in North Vancouver. It was slightly heartbreaking to drive past the entrance to Whistler twice and not go in, but there was only so much we could do.

You could rent a cheap motel room in central Vancouver, never drive for more than an hour and hit a different set of trails every day, with a craft brewery, a hearty meal and a helpful bike shop just minutes away from any of them. That’s before you even thought about venturing a little further to Squamish, Whistler, Pemberton, Revelstoke, Vancouver Island, the Sunshine Coast…

I feel like I just scratched the surface a tiny bit, and that’s after six days riding in four different locations. Cheap? No. Worth every penny? Absolutely.

So next time you’re thinking about the Alps, or Moab, or Colorado, make sure you put BC on your list too.

I’m already thinking about how I can get back…

Thanks to Rocky Mountain https://bikes.com and http://www.hellobc.com for their help with this trip.

By IMB